The Waves Of Disease

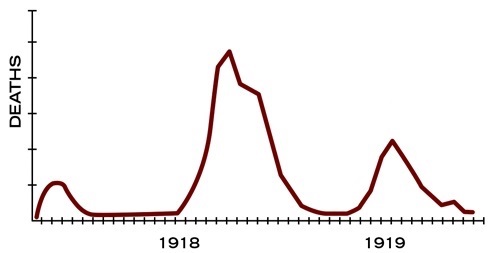

“There were 3 different waves of illness during the pandemic, starting in March 1918 and subsiding by summer of 1919,” according to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “The pandemic peaked in the United States during the second wave, in the fall of 1918. This highly fatal second wave was responsible for most of the U.S. deaths attributed to the pandemic.” (This graph was provided courtesy of the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

“There were 3 different waves of illness during the pandemic, starting in March 1918 and subsiding by summer of 1919,” according to the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “The pandemic peaked in the United States during the second wave, in the fall of 1918. This highly fatal second wave was responsible for most of the U.S. deaths attributed to the pandemic.” (This graph was provided courtesy of the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

Earlier this month, The Chronicles Of Grant County detailed some of the impact of the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919. How schools in Silver City were closed for weeks. How public gatherings were banned throughout New Mexico. How Native Americans, in particular, were devastated through this pandemic.

According to the United States National Archives and Records Administration, “In one year, the average life expectancy in the United States dropped by 12 years.”

In this edition, we’ll explore how the impact of that influenza pandemic actually came in 3 waves and then continued for 38 more years.

It’s important that when people today are being told that there is a need to “flatten the curve,” it does not mean that officials believe they can stop the spread of this pandemic – the pandemic of the coronavirus, Covid 19.

It means that the leaders want to suppress the initial wave of the disease in the United States so that the health care resources – hospitals, medical equipment, and doctors and nurses – are not strained beyond a point where they would have to officially ration care. Where leaders would officially have to decide who would get the needed medical resources – and have the best chances to live – and who would be denied medical resources – and likely suffer more and potentially die.

Looking back at what happened in 1918 and 1919, the three waves produced different results. The first wave in the Spring of 1918 was bad. Many died. But it was during the second wave – in the Fall of 1918 – that true devastation hit the United States. The third wave – in the Winter of 1918-1919 and Spring of 1919 – was not as deadly as the second wave, but it nonetheless caused suffering and death among the American people.

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that the virus that caused the pandemic of 1918-1919 then continued “to circulate seasonally for 38 years.”

In 1918, the United States was deeply involved in the Great War. Battles raged throughout Europe. Americans fought alongside British, French, and other nationals in a war that later became known as “World War I.” It was “The war to end all wars.”

How this influenza originated is not known for certain. According to the CDC, “The first outbreak of flu-like illnesses was detected in the United States in March [of 1918], with more than 100 cases reported at Camp Funston in Fort Riley, Kansas.” Reports indicated that the first Americans got sick from this flu in southwest Kansas in January of 1918. Men from southwest Kansas, likely infected with the virus, then reported for duty at Fort Riley. The outbreak at Fort Riley then followed.

Whether the influenza originated in Kansas or originated elsewhere, health officials indicated that the disease spread through military transports that moved hundreds of thousands of Americans throughout the United States and to and from Europe. The Library of Congress reported that more than 1 million Americans served in military units in Europe during World War I. As the virus spread, some of the military personnel came back to their hometowns unwittingly bringing an invisible killer with them.

One of the problems at that time, according to the CDC, was that “many health professionals served in the United States military…[overseas], resulting in shortages of medical personnel around the United States. The economy suffered as businesses and factories were forced to close due to sickness amongst workers.”

To put the times in perspective, life seemed “normal” at the New Mexico Normal School (now known as “Western New Mexico University”) on September 20, 1918. The Evening Herald of Albuquerque reported that the Normal School was conducting a story hour for children in Silver City on Sunday afternoons at the D.A.R. Park.

As the pandemic arrived in Grant County, schools in Silver City and elsewhere were closed. According to a news article dated November 24, 1918, in the Albuquerque Morning Journal, “Miss Martha Piotrowski, head of the English department [of today’s Western New Mexico University], has been rendering splendid service as a nurse since the close of school.” The news article explained that Miss Piotrowski was among a group of volunteers from Silver City who went to Mogollon to help the local folks there. The Albuquerque Morning Journal reported that 10% of the population in Mogollon died from the influenza pandemic.

No one knows for certain the actual number of people who died at Mogollon.

The CDC reported that the third wave of sickness and death occurred during the Winter of 1918-1919 and the Spring of 1919. While this pandemic ended during the Summer of that year, the virus that caused this pandemic, as noted previously, came back seasonally for 38 more years. Sickness and death because of this virus continued each season – just not at the levels experienced during 1918 and 1919.

It remains to be seen whether today’s pandemic will come in waves as in 1918-1919. Leaders are striving to “flatten the curve” so that the health care system is not overwhelmed. Those efforts will likely mean that the pandemic will last for some time as the disease spreads from person to person.

People in 1918 and in 1919 had far less resources than we do today. Knowledge of diseases was more limited at that time. Yet, Americans persevered. They met the challenges. They survived as a society.

If the patterns of past pandemics in modern history hold for the Covid 19 Pandemic, most people will survive. Unfortunately, heartache, sickness, fear, and death will be part of that survival process for the United States.

A street car conductor is seen here in Seattle not allowing a passenger on board without a mask in 1918.

A street car conductor is seen here in Seattle not allowing a passenger on board without a mask in 1918.

“Mass transit systems, with crowds of people in close quarters, were fertile venues for the spread of disease,” noted the United States National Archives and Records Administration. “In Seattle, public health officials required passengers and employees wear masks as a precautionary measure.” (The photo was provided courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration.)

Do you have questions about communities in Grant County?

A street name? A building?

Your questions may be used in a future news column.

Contact Richard McDonough at chroniclesofgrantcounty@gmail.com.

© 2020 Richard McDonough