[Editor's Note: This is timely, as the annual Pie Town celebration takes place this weekend Sept. 9, 2023.]

[Photo credit for all photos to Russell Lee Courtesy of the Library of Congress.]

[The PDF letters are Courtesy of the Roy Stryker Collection at University of Louisville. The text of each is also included in the article, but reading old script is always interesting, this editor believes.]

By Jim Arwood

When first I drove through this settlement in western New Mexico highland country, COVID-19 restrictions were in place. The handful of businesses lining the US60 were closed for health precautions.

My map denoted this was the spot where the road crosses the Continental Divide, but this place is more than a geographic crossroad.

Four months later, July 2021, I passed through again. The state’s indoor dining restrictions lifted, I stopped for lunch. A waitress told me how this town got its name.

A World War I vet named Clyde Norman built a log and mud shack on this unpaved stretch of highway and opened a gas station. Before long he started serving coffee and pie to those who passed by. The longhaulers dubbed the place Pie Town, and the name stuck.

A decade after its founding, families fleeing the Great Depression or blown away by the Dust Bowls of Oklahoma and Texas made Pie Town their destination. It was one of the last opportunities to homestead in the continental United States.

These homesteaders were dirt poor refugees. They accepted the government’s offer of land and in return they promised to fence it, build a house and dig a well within six months. Their houses were primitive dugout cellars covered with pinyon poles and a half-foot of dirt. Some managed to eke out a living farming.

I would pass through here three more times on my way to someplace else, until one day this place became my destination.

Welcome to Pie Town

It has been more than 80 years since a hand-written letter arrived in the Farm Security Administration (FSA) offices in Washington D.C.. It was postmarked: Pie Town, New Mexico, September 27, 1940.

Dear Roy –

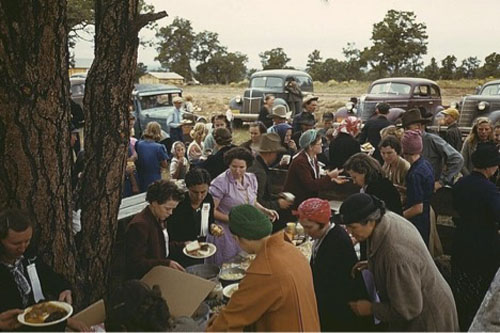

Arrived here about noon today and found Pie Town getting all set for its annual fair. It is a small one but there is a fine spirit here. Just after lunch it started to rain and rained hard all afternoon. The community is in the midst of its harvest season – they’ve had good crops of beans and corn and the vegetables they grow are really amazing for their large size and quality. . . .

My recent discovery of Pie Town paralleled that of the letter writer, Russell Lee. Lee was 37 years old that autumn of 1940. While the Great Depression bound most Americans to their jobs by necessity, Lee had inherited Indiana farmland some years earlier that gave him the economic freedom to pursue whatever interested him. That interest was photography, and he used his cameras in the employee of the US government to document far-flung Americans’ efforts to recover from the Depression.

Lee and I, separated by eight decades, drove the same route, looking for same thing: The American Spirit.

It was Friday, September 9, 2022, and I was 20 miles from Pie Town when a hard rain began to fall. My wipers fought a losing battle to keep the windshield clear and the road visible. Remnants of a Pacific hurricane, forecast to last the weekend, not only made driving difficult but threatened the weekend festival and harvest moon dance in Pie Town.

By the time I reached town the evening’s pre-festival activities were underway. Two years had passed since this celebration was last held, and I couldn’t help but think what the pandemic had canceled would surely not be scrubbed by rain in 2022. After all, this community, these people, have a history of resiliency.

A lull in the storm brought a respite, allowing volunteers to erect barricades to cordon off dirt road residential back streets from the anticipated crowd of festival goers.

In the park people gathered around the makeshift Potato Bar for dinner -- a baked spud with a choice of toppings. Kids lined up behind the playground’s old metal slide to shoot the chutes. Sliding over and over again. And again. The straight-chute was so slippery I feared they might slide right off the mountain.

A girl of five or six completed her turn and ran to get back in line, excitedly yelling my way, “I hope you’re having fun!”

She did not wait for my response.

Across the highway the orange harvest moon rose above the shadows of the tree-line and made a fleeting appearance before being swallowed by dark clouds.

This was not the first time this festival had been blessed with rain. Russell Lee’s decades old note to his FSA supervisor, Roy Stryker, described a hard autumn rain on the eve of the 1940 Pie Town fair.

Stryker, the head of the FSA’s Historical Section Division of Information, had launched the division’s photography program five years earlier, assembling what is considered the most famous team of photographers in American history to document rural America in the Dirty Thirties. Dorothea Lange was among his first hires.

Lange’s iconic 1936 photo, “Migrant Mother,” portrayed two children, faces buried in their worried mother’s shoulder, had become emblematic of the era’s migrant farm worker. Russell Lee joined the team two years later.

Lee passed through Pie Town for the first time in the Spring of 1940 -- on his way to someplace else. Within minutes of sitting down for a sandwich at the Pie Town Café, Lee met Joe Keele, a storekeeper and president of the local Farm Bureau. After lunch Lee continued to his destination, Phoenix. But he was intrigued by his chat with Keele. Upon arriving in Phoenix, he wrote Stryker to tell him about the migrant settlement on the Continental Divide, where the tree line breaks.

April 20, 1940

Phoenix, AZ

Dear Roy –

Arrived here yesterday evening after a trip thru about all the extremes you could imagine – windstorms, rain, dust storms, sleet, driving snow and finally tropical heat. From Albuquerque we went to Socorro to Datil, N. Mex . . . Then we crossed the continental divide and on to Pie Town which is a settlement of migrants from Texas and Oklahoma – dry land farmers raising Pinto Beans and corn. Talked with the store owner there and I believe it should be one of the communities we must cover. He called it the last frontier with people on farms ranging from 30 to 200 acres – some living in cabins with dirt floors – others better off but all seemingly united in an effort to make their community really function . . .

Best Regards

Russell

Over the previous three years, Lee had mailed scores of such missives to Stryker, nearly always from someplace new. The ongoing correspondence reflected an eyewitness account of rural America’s ascent from the depths of economic calamity. His letters described the people he encountered, where they came from, their toils, their crops, their churches, schools, festivals, stores, and the government programs that provided some relief.

Stryker respected his photographers’ ability to find authentic subject matter and when Lee’s April 20th letter identified Pie Town as a community “they must cover,” he was quick to reply.

April 22, 1940

Washington, D.C.

Dear Russell:

Your letter of 4/20/40 arrived last night . . . Pie Town sounds most interesting. By all means put it on your agenda. If, after you have sampled it, it still seems as good a story as you indicate, then we should encourage someone to write it up, and offer them the pictures to go with it. I am always rather skittish about COLLIER’S, but perhaps we could get them to do it. If not, LOOK, or perhaps the NEW YORK TIMES MAGAZINE. You will, of course, get a pretty complete story on it, which we could submit to any of these agencies. The photographs, as far as possible, will have to indicate something of what you suggest in your letter, namely: an attempt to integrate their lives on this type of land in such a way as to stay off the highways and the relief rolls. I suppose the storekeeper was right – a “last frontier”. I suspect you had better look pretty carefully under this phrase, sometimes we get fooled by their “last frontiers”.

Sincerely yours,

Roy E. Stryker

In May, Lee passed through Pie Town again enroute to somewhere else and gy now he was convinced this was indeed the real deal, the “last frontier.” He returned twice in June to photograph all phases of life here.

By mid-summer Lee’s Pie Town photos were making the rounds in Washington, D.C.. The images illustrated a group of people helping each other build houses and plant crops. They highlighted the community they built together, store shelves stocked with life’s necessities and families with food on their tables.

It was a far different narrative than the story of California migrant farm workers unable to make ends meet. These weren’t “Pickers,” living from harvest to harvest, residing in shantytowns and government relief camps. Pie Town stood in stark contrast to Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother,” or the account conveyed by John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath.

While Roy Stryker set about pitching Lee’s photos of Pie Town to national publications, the congressional Tolan Committee had also become aware of the Pie Town photos and the story they told. Established by the U.S. House of Representatives in April 1940, the Select Committee’s “Dust Bowl” hearings were investigating migration and the needs of the poor, as well as the effectiveness of government programs established to respond to those needs.

Their interest in Pie Town stemmed from the fact that this group of Texas and Oklahoma drought refugees had managed to build a new life when given the opportunity to obtain land.

The Committee held hearings throughout the country, hoping to gain an understanding of how society could better treat migrants.

Hundreds of witnesses testified to the causes, problems and solutions to the migrant crisis of the 1930s. Witnesses came from everywhere, from all walks of life. They weren’t just farmers. They came from cities, too. They were woodworkers, butchers, waitresses, steel workers, plumbers. Experts from relief organizations and government agencies also testified and submitted reports of their findings.

Pie Towners were invited to testify at the committee’s final hearing in California at the end of September, 1940. But the dates conflicted with their harvest and annual fair, and the committee never did hear from the Pie Town migrants.

Minus the Pie Town story, the California hearings largely dealt with the California migration. The committee heard of makeshift settlements consisting of cars, shacks, tents and trailers. Testimony from the FSA detailed efforts to establish temporary government camps of small houses on small plots. The committee heard how government programs offered advice to migrants on cultivating small acreages using tractors and other modern equipment.

They heard stories of citizens looking for work as day laborers and pickers. About trucks appearing in the morning and everybody climbing aboard. When the growers had the number of workers needed, they drove away.

Whether it was fruit and vegetable pickers in California’s valleys, or along the eastern seaboard, these migrants all faced similar problems: Housing, health care and education.

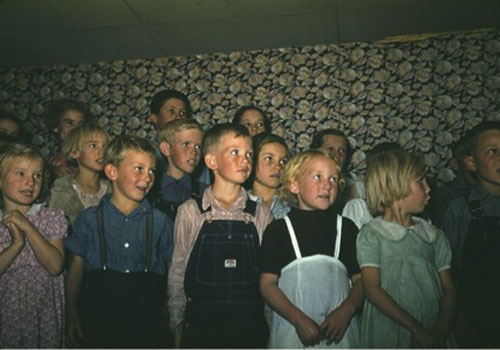

Migrant children lacked the educational opportunities and facilities available to children who stayed in one place and had a home. Most rarely saw the inside of a schoolroom for more than a year. When children did go to school it was usually for a short time, and then they dropped out again, moving with their family from temporary camp to camp as they followed the harvest.

Unfortunately, Pie Town, which dealt with these same problems, never got to tell its story on the tableau it deserved. There was no government report entered into the Tolan Committee’s record of their experience. Nobody from Pie Town appeared as a witness at a hearing, either.

Nor was there a photo-essay to tell their story. National media outlets had turned their focus to a new wave of migration – people thronging to cities in search of defense industry jobs as the nation prepared for war.

Four generations later, the story of Pie Town and its milieu, raw and untouched, still waits to be told.

There were no farmers living here when Clyde Norman built his gas station in 1922 -- they started arriving in the 30s. Those that came first helped latecomers locate land to homestead, to build houses and dugouts, and gave them canned goods if they needed food to get by. They taught each other the nuances of the short growing season and how to farm at an elevation of 8700 feet.

The local beanery stored their crops and loaned them money at no cost, and didn’t charge a cent to truck their harvest to markets in Socorro or Albuquerque.

When the state refused to recognize their school district, they all pitched in and built a school, hired a teacher, and made sure there was no interruption in the education of their young. They took turns driving youngsters into town to attend school.

They had get-togethers. Community sings. Square dances. Literary society meetings. They played dominoes, had pie suppers, everything they used to do where they came from.

And, they owned their land.

But their narrative was never fulsomely told.

Russell Lee's Pie Town photos were finally published in a national magazine in October 1941. U.S Camera published a six-page spread that focused primarily on the technical aspect of his photographs.

It's been more than 80 years since Pie Town was briefly on the national scene, and on this morning, Saturday, September 10, 2022, a couple thousand people have traveled back in time to celebrate this legacy.

Skies are clear as far as the eye can see. Runners stream through the back streets as the Pi Run kicks off this annual festival. Bakers line-up at the fire station to drop off their pie contest entries. Vendors are set up in the park selling everything from arts and crafts to pies, whole and by the slice. In the pavilion the tables are ready for pie eating contestants. Music springs from the stage.

The festival’s queen announcement comes as a complete surprise to the winner, Margaret. She is joined on stage by past queens who congratulate not only her, but each other on keeping it a secret from their friend. Among those assembled on stage is 96-year-old Katharine McKee Roberts. She was just a teenager when Russell Lee snapped her photo as she sang with her Pie Town classmates in the summer of 1940.

As festival royalty leave the stage, I attempt to reach Katherine, wanting to introduce myself and ask her a question. But the nonagenarian, escorted by her daughter, encounters a bevy of friends and well-wishers, delaying her departure. When she finally breaks free, I overhear her saying how she needs to get home as everyone is gathering at the farm. I manage a “Hello” as she passes, but eat my question.

Yet everything I want to know is told by the smile on her face and the sparkle in her eyes: Despite the passage of decades, all that has really changed in Pie Town are the names and the faces. Like Russell Lee wrote Roy Stryker on September 27, 1940, “There is a fine spirit here.”

And as if by cue, I overhear someone behind me say the town’s pie guardian, Kathy Knapp, helped the crew at the nearby Pie-O-Neer restaurant, make more than 500 pies for this year’s festival.

By early afternoon, just as the horn toad jumping contest crowned a new champ, the wind began to bluster. The temperature dropped. The out-of-town crowd headed to their cars lining the highway and began the slow procession down the mountain.

Up on the hill a band from Socorro tuned up in the Community Center. There were at least a hundred people inside for the harvest moon dance. Outside, clouds threatened. The moon was a no show. Lightning illuminated the sky. It’s time I left.

Russell Lee left Pie Town for the final time on October 4, 1940. In his camera bag were three rolls of color Kodachrome film documenting the Pie Town fair.

His last letter to Roy Stryker, postmarked after the fair (9/27/40) described the town’s reaction to his black and white photos that were on display during fair. It was the first time Pie Town had seen any of the photos he had taken during his previous visits.

. . . the pix you sent out are certainly appreciated by the community. I don’t believe that you could ever get a more enthusiastic crowd for an exhibit. I tacked them on the walls for everybody to see. The Farm Bureau is going to keep them intact so they may have a good historical record of what Pie Town looked like in 1940.

Russell