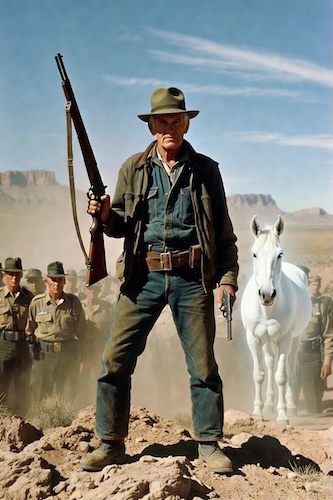

Image by Grok

I would like to tell you a story today that came to mind after I wrote the following letter to the editor a few years ago. It went something like this:

Dear Editor,

I must agree with those who have expressed bewilderment as to why the military is using the skies over our wilderness areas for combat exercises. I, as an individual citizen, cannot drive a motorized vehicle into a wilderness area, but a jet can fly in and scare the bejesus out of every living thing in its path, starting wildfires and littering the forest with debris!

My question is this: why not use the White Sands Missile Range for their exercises? That was why it was forcibly taken from ranchers so many decades ago. And a lot of that, I believe, was excessive use of eminent domain to steal private property, but that is a story for another day.

Today is that day.

Date-line — 08/07/1957

Bill Montgomery

El Paso Times

Deputies Fail To Get Rancher Off Range Area

Prather's Ranch, N.M. – John Prather loaded up his 30-30 Winchester and .38 automatic pistol late Tuesday to face up to a new day's battle with the U.S. deputy marshals he refused to let take him off his ranch.

Meanwhile, two Ft. Bliss colonels, and five military policemen were reported ready to join the marshals at daylight. The later news leaked out after newsmen's automobiles finally were allowed through roadblocks after being sealed inside the vast McGregor guided missile range by Army roadblocks.

U.S. District Judge Waldo Rogers in Albuquerque Tuesday morning issued a writ of assistance which deputies of U.S. Marshal George Beach were supposed to use to force the fighting rancher from his home... But it didn't work. The deputies failed to lay a hand on the 82-year-old Prather, who warned if they ever touched him, he would fight until they killed him... "I'm going to stay here, dead or alive," Prather said with the same rugged determination which has held off the U.S. Army from taking his range home for two years.

Judge Rodgers was quoted Monday as saying he "had serious doubts" about whether he had done the right thing in giving Prather's land to the Army, because it appeared the Army might not need it.

While confronting the quartet for about three hours, the crusty rancher repeatedly warned them not to put a hand on him, and none did. "By damn, if I had a job where some judge could tell me to go out and kill a man, I'd quit it before I'd kill him if he was in the right like I am," Prather told the deputies.

"We don't want to kill nobody," a marshal said defensively. Throughout his interview with the marshals, the tough, outspoken rancher took care to keep any of them from getting behind him and kept on his feet except for the last few minutes.

About 3:20 p.m., Mrs. Mary Toy, Prather's housekeeper, served coffee for a reporter and Deputy Marshal Frescas. Prather then sat on a cottonwood stump, made Frescas take a chair with arms on it, and faced a direction where he could watch the other two officers.

Frescas said he enjoyed the coffee. Prather said: "I'm glad you do, sir. I want to be friends with everybody. Why don't you go tell that judge that I'm not going to leave, and it's time for him to back down and change that court order?"

"How in the world can a judge who admits he has doubts order a man to leave his home that he has worked all his life to build for his family?"

Relatives Gather – Tom Prather, Anthony, N.M., farmer-rancher, presumably notified by his sister, was expected to hasten to the ranch. The word for reinforcements went out Tuesday night. A mob of Prather's closely-knit clansmen and other well-wishers was expected for Wednesday's session, unless they are kept away by the cordon of Ft. Bliss troops rimming the ranch.

Col. Baughn, whom Prather refers to as "Col. Bull," and Cobb, tagged "Smilin' Johnny" by the rancher, left soon after the first reporter arrived at the ranch on Tuesday. "'Smilin'' Johnny has plumb wore his smile out a-tryin' to talk me into sellin' my birthright," Prather said in reference to the Corps of Engineers representative who failed to crack a smile all day... "I'm stout enough that they'll never haul me to town in a car alive," he said. "I'll guarantee you that." Never, throughout the long and rugged day, did the indomitable rancher waver from his stand that he would die rather than leave or be moved.

"I'd like to live a while yet," he told the solemn-faced peace officers, "but I'm not moving, by damn, and if it's time for me to die, I'm ready. Let's get on with it." At one point, the nearly-blind rancher – who used to shoot crows off fenceposts from a moving automobile with a pistol – issued a direct challenge to one of the marshals for a personal shoot-out in the finest Old West tradition.

"Just let me get my gun, and we'll square off and have at it," he said. "I'm ready any time you are." The marshals, already bemoaning their fate at being assigned to the job, wanted no part of it.

Date-line — February 13, 1965

Old John Prather will be buried tomorrow on the ranch that he refused to surrender to the Army – with the Army's blessing.

His daughter and son-in-law, Mr. and Mrs. Hart Gaba of El Paso, got permission to bury the pioneer cattleman at a spot he himself selected before his death. It is a few feet from the ranch headquarters house on the Army's McGregor Missile Range.

Mr. Prather died yesterday – not at his ranch as he had wished but at the home of Mrs. Daisy Speers at Boles Acres, six miles south of Alamogordo, N.M. He was 91 and individualistic to the end, but death came quietly.

Today, Maj. Gen. Tom V. Stayton, Ft. Bliss commander, was on record with the statement: "I am very sorry to hear of Mr. Prather's death. He was a great pioneer of the West. Certainly, we have no objection to his burial there. How could we?"

The Gabas already have fenced off a plot, 25 by 50 feet for the old rancher's private cemetery. The site is about 80 miles northeast of El Paso on the 40-section ranch that Old John defended with his rifle against Ft. Bliss troops in 1957. He had been ranching there since the turn of the century, and he vowed he would never leave or turn it over to flying missiles, which he called "contraptions" that the Government "brought out here just to try to scare me."

The Army, wanting his 40 sections for McGregor Range, backed off when Old John threatened to shoot. An uneasy truce and litigation ensued.

Finally, the Government sent Old John a check for $106,000 for his ranch. He fired it back. The Government placed the check in an Albuquerque bank, and it is still there uncashed.

The Army moved its missiles in. Old John refused to move out. He refused to move his cattle out, "come missiles, hell or high water."

Sen. Clinton P. Anderson of New Mexico got a bill passed in Congress allowing Prather to live out his lifetime on a 15-acre reservation on the ranch. The old rancher continued to graze his herds. "I've never moved out a single cow," he would say. "I've been here 53 years," he said in 1959, "and I'm going to die here."

But in March of 1963, the rugged old cowman got pneumonia, becoming desperately ill. His daughter, Mrs. Connie Gaba, and Mr. Gaba were living at the ranch house then. "He didn't want to leave for a hospital," Mr. Gaba recalled. "He said he wanted to die in front of the fireplace there in the house."

Mr. Gaba picked him up in his arms and took him to an Alamogordo hospital. The old man was never the same again. He became semi-paralyzed and return to the ranch was out of the question. The Gabas placed him with Mrs. Speers, who provided tender care until his peaceful death at 8 a.m. yesterday. "He just went to sleep after breakfast," she said.

Death halted plans for a court hearing to act on a plea by Prather's son, Tom Prather of La Mesa, N.M., that the old rancher be declared incompetent and he himself named guardian. This was opposed by Mrs. Gaba.

Old John left a will naming a neighboring rancher, Don Potter, as executor. It will go to probate and the estate will be divided.

And tomorrow, the family united in respect and sorrow will join with friends and neighbors in a farewell to Old John Prather, who will rest forever on the ranch he loved.

Well, there you have it, friends. Old John is gone, but his legacy of rugged individualism lives on. And to this day, visitors to the gravesite say they sometimes see the mirage-like vision of John's favorite white mule lingering there, near his grave.

Supposedly, the mule was lost when John left the ranch and was occasionally seen on the range by government line riders. If true, that would be one old mule by now. But hey, ghosts live forever, don't they?

Reflection: The Wilderness Above Us

When I wrote my letter to the editor a few years ago, I asked a simple question: Why is it that a citizen cannot drive a motorized vehicle into a wilderness area, but a jet can roar overhead, rattling the bones of every living thing beneath it? Why is the land protected from us, but not from those who claim to protect us?

At the time, I hinted that this question had a history— a long shadow cast by decisions made decades ago. John Prather's story is part of that shadow.

His last acre was not taken for a school, or a hospital, or a public good that would bless generations. It was taken for convenience— because the Army wanted more room to test its "contraptions," and because one old rancher seemed too small to matter.

Today, the wilderness faces a similar logic. The rules that restrict ordinary citizens do not bind the powerful. The land is sacred when we approach it, but expendable when they do.

Jets can scream across the Gila. Supersonic booms can scatter elk herds. Debris can fall where a man cannot legally walk with a chainsaw. And when we ask why, we are told—again— that it is "for the good of the nation."

John Prather heard that phrase, too. But he knew something we are in danger of forgetting: that the land is not merely acreage, not merely coordinates on a map, not merely empty space waiting to be used. It is a memory. It is an inheritance. It is the last acre of a people's dignity.

When the wilderness becomes a training ground, when the sky becomes a weapons corridor, when the rules apply only to the ruled— we are no longer talking about land use. We are talking about the slow erosion of stewardship.

Prather stood his ground because he understood that once you surrender the meaning of a place, you soon surrender the place itself. And so, his story becomes a parable for our own moment, right here, and right now.

We may not face deputy marshals at our gates, but we face decisions made far away by people who will never walk the trails they disrupt or hear the silence they fracture.

The cost of standing your ground is real. But the cost of never standing at all is far greater. If we don't speak for the wilderness, who will? And if we do not guard the last quiet places, we will wake one day to find that the last acre is gone— not taken by force but surrendered by silence.

John Prather's stand reminds us that some things are worth defending even when the world calls them expendable.

The land remembers. And so should we.

There once was a man named John,

with a body and soul full of brawn.

His mules he once supplied to the army fort,

but now they want his ranch for a missile port.

They speak those words of eminent domain,

but John Prather stood fast, and not in vain.

For the Army believed the devil's lie,

and thought him old and soon to die.

But the man was tuff and shed no tears,

he fooled them and lived ten more years.

The missiles fly high, and the shells fly low,

but now, over John Prather's grave they go.